Scalloping in the Gulf of Mexico

Florida’s bay scallops occur in isolated populations scattered along its west coast, and the majority are found in nearshore seagrass beds from Tarpon Springs in Pinellas County to Port St. Joe in Gulf County.

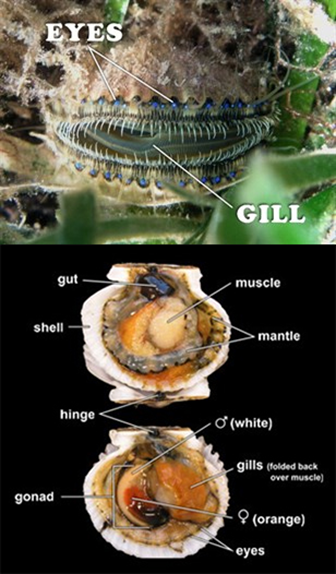

The bay scallop is a member of phylum Mollusca in the class Bivalvia. Bivalves have two valves, or shells, joined by a hinge.

Scallops in the Gulf of Mexico are generally colored gray or gray brown with radiating rays on the upper shell. The lower shell is typically white, but in about 4% of the population can be bright orange and about 1-2% of the scallops are lemon yellow. Many shell collectors seek the “colored” scallop shells.

Bay scallops can reach a shell height of 90 millimeters (3.5 inches) and live up to two years. In Florida, however, bay scallops rarely grow larger than 75 millimeters (3 inches) or live longer than one year.

Bay scallops feed by opening their shells and filtering small particles of algae and organic matter from the water. Bay scallops also open their shells when breathing, using their gills to pull oxygen out of the water. Bay scallops close their shells to protect themselves from predators and to prevent silt from clogging their delicate gills, which would result in suffocation.

Bay scallops have many tiny, blue eyes lining the outer rim of the shells to help detect movement and serve as a warning system. When threatened, a bay scallop can swim backwards by contracting and relaxing its large adductor muscle to open and close its shells. This thrusts out water and propels the scallop up off the bottom and away from danger.

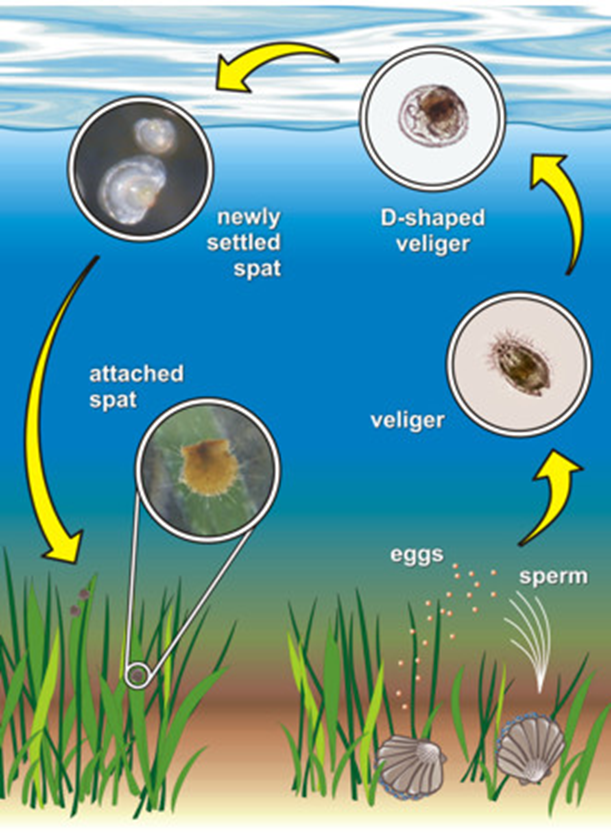

A bay scallop has the remarkable ability to develop female and male sexual organs and, thus, produces both eggs and sperm. In the final stages of development, scallops use all their energy for reproduction. This leaves little energy for movement, making the scallop vulnerable to predation. This may be why many do not survive to spawn a second time.

Rapid changes in water temperature generally trigger bay scallops to spawn. In Florida, most spawning occurs in the fall when the temperature drops. A single scallop is capable of producing millions of eggs at once, but only one egg out of 12 million is likely to reach adulthood.

It takes approximately 36 hours for fertilized eggs to become tiny larvae, known as veligers. Larval scallops are pelagic, meaning they drift in the water column, for 10 to 14 days. During that time, they may be carried a considerable distance from where they were spawned. While drifting, larvae develop into juvenile scallops, commonly called spat. They eventually settle out of the water column and attach to seagrass blades using thin, silky fibers called byssal threads. Approximately 90 percent of spat will die within six weeks of settlement. Those that survive eventually detach from the seagrass and fall to the bottom, where they remain for the rest of their lives.

2020 Annual Abundance Survey

Each summer, biologists assess bay scallop populations along the Gulf Coast of Florida, located in open and closed recreational harvest areas. Surveys are usually initiated in June and completed in July. Scientists look at long-term trends in the abundance of scallops in both the open and closed areas and present those findings to the Division of Marine Fisheries Management.

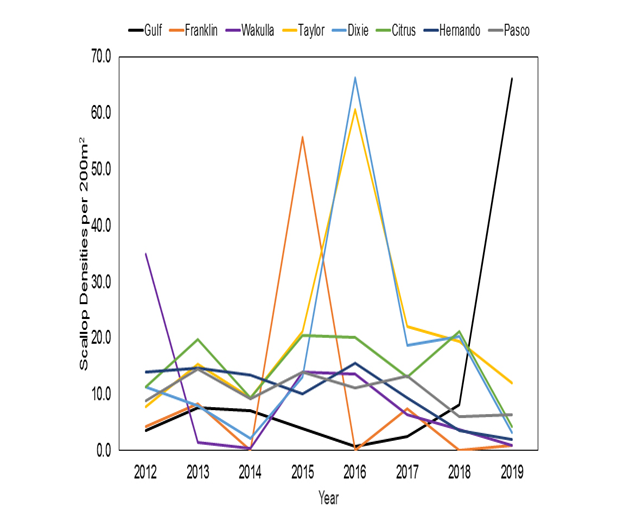

There are eight counties that are surveyed within the open harvest area: Gulf, Franklin, Wakulla, Taylor, Dixie, Citrus, Hernando and Pasco. The graph below illustrates the average number of scallops observed per 200 square meters in those counties from 2012 to 2019. Scallop population abundance is highly variable because scallops live for only one year and are sensitive to changes in water quality, like salinity. Abrupt changes in scallop population abundance may occur after major environmental events such as an El Niño, hurricanes or tropical storms.